JEWISH

EAST END OF LONDON PHOTO GALLERY & COMMENTARY

London's East End Synagogues, cemeteries and more......

My personal journey through the Jewish East End of London

House of a

Thousand Destinies - The Jews Temporary Shelter,

adapted from a talk by a former J.T.S. employee Prue Baker....but

first, a letter from the USA about a 1971 honeymoon night spent in

the Jews Temporary Shelter, Mansell Street:

July 30 2012, Hello Phil,

I wonder if you can help me locate an old Jewish

establishment in London's East End. In 1971 we spent our honeymoon

travelling around Europe and Israel. We arrived in London right

before Shabbat and called all the tel #s we had been given. None of

the known Jewish hotels/hostels had room for us. Someone suggested

a place called The Jewish Refugee Home. The administrator said we

could stay for Shabbat and have meals there but we must see it first

in case it did not meet our expectations. This place had an entrance

level and then two further levels with the men's dormitory on one

floor and the ladies dormitory room on the next floor. As I recall,

there was one bathroom per floor. There were only a handful of

people staying at the time. This is the way we spent the first

Shabbat of our honeymoon. Sometimes the most unexpected experiences

make the best memories. The only other thing I remember from 40

years ago is that this Jewish Refugee Home was quite near to

Petticoat Lane and we were sent there on Sunday morning to see the

giant "Jewish" street Fair and Flea market. Since your family comes

from this area I wonder if the place I am describing is familiar to

you,

and if it still exists. Thanks you for taking the time to read this

email. We would love to hear from you if you have any idea about

our "Honeymoon Hotel".

Sincerely, Pamela & Harold Falik, New Jersey, USA

House of a

Thousand Destinies - The Jews Temporary Shelter,

adapted from a talk by a former J.T.S. employee Prue Baker

It was in the spring of 1885

that a poor immigrant called Simon Cohen the Baker, known as Simon

Becker, opened part of his premises in Church Lane, Whitechapel, to

provide a refuge for homeless, jobless immigrants from the docks. It

was the time of what was known as the great migration from

eastern Europe which was to change forever the make-up of

Anglo-Jewry.

The Jewish Board of Guardians

deemed the Becker shelter unsanitary and closed it. It is described

in a letter to the Jewish Chronicle in 1885.

“Its abject misery is worse than

any workhouse and it provides less food. There is absolutely no

sleeping accommodation except a wooden floor. The only kind of

daily food is rice and tea and bread and this is very irregular.

Let us get a ‘responsible committee’ or let a few gentlemen see if

they cannot get a few cheap mattresses for the older men to lie upon

at night and some blankets or rugs.”

Such protests from people who recognised the need for

such a shelter led to a public meeting at the Jewish Working Men’s

Club, and soon after another shelter was opened in Leman Street,

promoted by three wealthy and influential Jews led by Hermann

Landau.

Landau (left:

contemporary sketch, Hermann Landau welcoming poor Jews to the

Shelter), who had arrived from Poland

in 1864 and became a banker and influential member of the Jewish

community, said it was to be “an institution in which newcomers,

having a little money, might obtain accommodation and the

necessaries they required at cost price, and where they would

receive useful advice”. Initially, funds came from the Rothschild

family and individual subscriptions, but in the coming years the

shelter was often on the margin of financial viability.

So the

first shelter opened in Leman Street on April 11 1886, moving later

to Mansell Street, both in the Aldgate area. The shelter used a

selection of lodging houses for those with some financial means,

and soon furniture contractors and landlords were approaching it

plying for hire. The Shelter also worked with the Soup Kitchen for

the Jewish Poor and other charitable bodies in the East End.

The

Poor Jews Temporary Shelter was a very functional title. And

indeed its function was to provide protection and temporary

accommodation for Jewish migrants, transmigrants and occasionally

the homeless and the non-Jew.

The

Poor Jews Temporary Shelter was a very functional title. And

indeed its function was to provide protection and temporary

accommodation for Jewish migrants, transmigrants and occasionally

the homeless and the non-Jew.

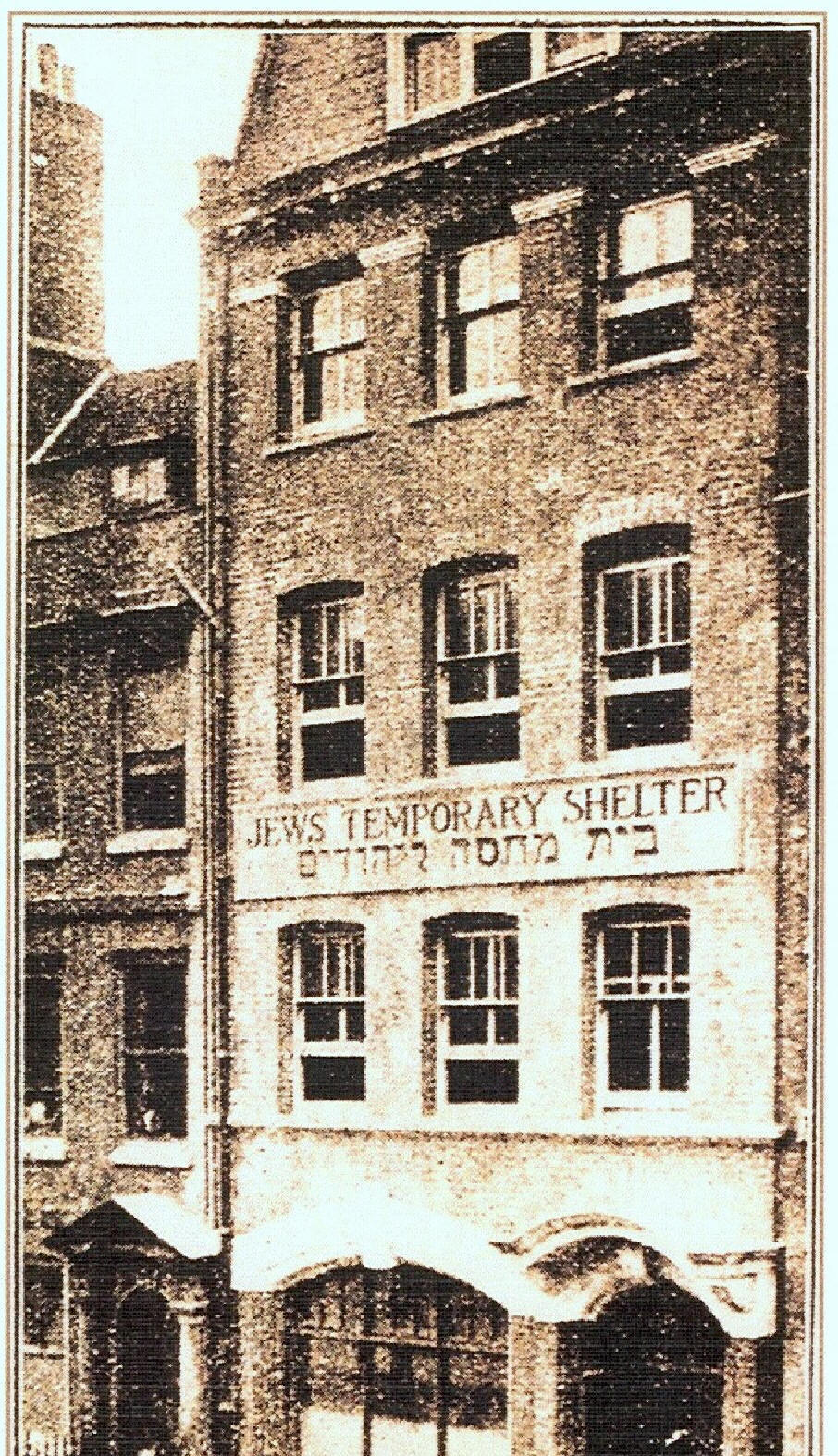

right: Jews Temporary Shelter when located in Leman Street

Within

the Jewish community, you might imagine that it would be seen as

entirely laudable and uncontroversial. But not so.

The

President and Council of the Jewish Board of Guardians and many

leading members of the Anglo-Jewish community such as Arnold White

strongly opposed this initiative, fearing that it would encourage an

influx of immigrants who would adversely affect their own lives.

There

was a move to contact rabbis in eastern Europe to ask them to

discourage economic migrants in particular, painting a dark picture

of unemployment and poverty that awaited in the UK. Jews who were

enjoying hard-won prosperity feared for their position and any

backlash against the immigrants that might sweep them up.

Nonetheless, there were a number of initiatives in the UK as well as

in continental Europe facilitating immigration and transmigration.

But the principal agency in the UK was unquestionably the Poor Jews

Temporary Shelter.

Landau responded to the opponents of immigration by

emphasising the health and work skills of the majority of immigrants

as well as their general preference for moving on to other

countries. He argued that assistance in establishing the shelter

had come mostly from poor Jews of the East End who were willing to

support the shelter with weekly subscriptions. The shelter would

be spartan in style and offer only temporary accommodation. He was

anxious to emphasise the basic character of the shelter.

Landau persisted in working for good relations

between the various Jewish charities and in the end they did rebuild

cordial relations, largely due to the calibre of those working for

the shelter.

His most convincing argument was that by protecting

transmigrants the shelter enabled them to journey forward to America

and elsewhere instead of being trapped in the UK. He estimated

that 40 per cent of those who wished to proceed to America or South

Africa were being prevented from doing so by dockside robberies,

and gave details of how the ‘crimps’ defrauded the ‘greener’ of

whatever cash they might have on entry. He also gave evidence to the

House of Commons Select Committee.

The shelter’s first annual report in 1886 reflects

the need to be on the defensive. In 1890, the annual report noted a

50 per cent increase in the numbers coming to the shelter. But it

also focused on statistics for how many people returned home and how

many emigrated successfully, concluding that successful

transmigration was increasing. “These figures,” said the chairman,

“are a complete answer to those who denounce the so-called Jewish

Invasion.”

By 1900 the mood was confident. The shelter had

found its role. The 1900/01 annual report stated that “ships

entering the Thames from Hamburg telegraphed to give their time of

arrival”. For many years the shelter’s superintendent was required

to meet every incoming ship in the Port of London that might be

carrying immigrants and to approach people to prevent them being

robbed or taken in sweat shops as slave labour.

Landau was asked why these victims did not

immediately seek police aid. He replied: “These poor folks feared

to call for the assistance of the police because they thought the

English police were much the same as the dreaded objescik

whom they had left behind.”

Soon after this the police did raid the shelter.

They claimed that, because it charged those staying there, it should

have been registered under the Common Lodging House Act and was

therefore breaking the law. The shelter had to stop requiring

payment, finding respectable lodgings for those who were able to pay

and giving the free accommodation to those without money.

The experience prompted Landau to suspect that the

police were in cahoots with those trying to prevent immigrants from

reaching the shelter. There is no evidence one way or the other

but it indicates the atmosphere in which the shelter operated in the

early days.

So this is the background to the foundation and early

days of the shelter. How did it operate, and what did it achieve?

In the 1890s a complex period of negotiation resulted

in the shelter’s acting as shipping agent for many major shipping

lines. This produced valuable income, in particular from the

shelter’s work for Union Castle Line shipping to South Africa. Many

of the Jewish settlements in South Africa originating from eastern

Europe passed through the administration of the shelter (as detailed

in the February 2008 issue of The Cable).

One aspect of its achievement is the sheer number of

people passing through London who had some contact with it. In 1900

the shelter had two hours notice of 253 Jews expelled from South

Africa by the Boer government. Five months later 650 arrived from

Romania. Between 1902 and 1905 the shelter processed 16,000

people. It chartered a special ship to sail to America. Every

individual needed careful questioning and identification,

involving many, many hours of painstaking work.

The Shelter soon gained a reputation for doing

sterling work in a responsible manner, developing skills in working

with the authorities to ensure the smooth passage of migrants.

Thus, in 1892 the superintendent went to Hamburg

following complaints that transmigrants’ luggage had been stolen by

shipping agents. As a result a Hamburg bureau was established and

there were no further complaints. In 1893 during a cholera outbreak

the Port of London Authority medical officer engaged the shelter in

helping to keep check on arrivals. In 1896 reports reached the

shelter of ill-treatment of emigrants at the Dutch frontier. They

had been robbed and their luggage taken, with extortionate sums

demanded for its return. Falsely high fares were being demanded

for tickets. The shelter complained to the Dutch consul and sent a

delegation to confer with the Dutch shelter organisation. The

delegation visited the ticket officials and made suggestions to

protect immigrants, after which there were no more complaints. In

1905 the Shelter established a system whereby letters shown by

transmigrants at German borders were sent to London to the shelter

for verification, so German shipping agents could no longer claim

they were false. The shelter also supervised the handling of

immigrants’ money at the German border.

On a less dramatic day-to-day level, one early

committee meeting records:

-

A letter of thanks to be sent to

police for assistance at a railway station

-

Payment of unpaid rent for an

immigrant who had defaulted

-

Accepting £5.00 from a local shul

for providing a minyan (nice little earner)

-

Concern about people being handed

over to missionaries because it was Shabbat. Need to involve

non-Jews on Shabbat and festivals.

However this period of intense activity came to an

end after 1905 with the passing of the Aliens Act. It was the first

time in peacetime that legislation had attempted to limit

immigration to the UK. When the Bill was debated in the Commons,

Herbert Asquith (Liberal Home Secretary) criticised it and made

mention of the large numbers of Russian refugees he had seen in the

shelter on a visit he had made shortly before the debate.

Nevertheless the Bill was passed and the shelter became involved in

attempting to ensure that it was administered fairly. It became

active with appeal boards, acting as advocates and translating

letters used in evidence. Shipping companies were now obliged to

take up bonds from would-be migrants and the shelter took on a new

and responsible role overseeing this and being paid for it. Any

commission taken from migrants (as distinct from agency fees) was

returned to them, although there was pressure to put the money

towards the shelter’s running costs.

In 1910 the shelter was asked by the Thompson Line to

handle several thousand non-Jewish migrants en route to the US or

Australia. In the same year an emigrant ship travelling to Canada

(where there was a labour shortage) caught fire off Dover. The

shelter was immediately called in to meet the returning train and to

look after stranded emigrants until another ship could sail. After

this incident the shelter reluctantly minuted that in future it

would be able to accommodate non-Jews only if it had spare beds.

In the years leading up to the First World War its

work continued, with immigrants coming mostly from eastern Europe.

There is a vivid account by Stefan Zweig of the sense of trepidation

felt by those leaving their country of origin. In 1903/4 for

instance, 5000 came through the shelter. There are a host of

stories filtering down through the reminiscence passed on to

descendants. During the war there were some immigrants coming

through via Belgium, but the main service resumed, as we know only

too painfully, between the wars and stories abound from this period

as well.

The word ‘Poor’ was removed from the shelter’s title

in 1914.

There were occasional unexpected crises in the

interwar years. In 1923 changes in US immigration law caused

thousands to be stranded in Britain and once again the shelter was

called in to help.

By

1937 the shelter had met 1,183,000 people at the docks and 126,000

had stayed at the shelter. An appeal in 1938 noted with pride that

sometimes as many as one third of those staying there were non-Jews.

By

1937 the shelter had met 1,183,000 people at the docks and 126,000

had stayed at the shelter. An appeal in 1938 noted with pride that

sometimes as many as one third of those staying there were non-Jews.

In 1938/9 alone some 8,000 people were helped by the

shelter. By now the shelter was covering railway stations as well as

the ports.

During the Second World War the shelter offered

temporary housing to people bombed out, until in 1943 the Mansell

Street building was requisitioned to house American troops, after

which the shelter was limited to an advisory service until the end

of the war.

In 1946 100 children from displaced persons camps

were received at the shelter as it continued to serve a useful

purpose, helping refugees from all over Europe. Refugees also came

from areas such as Aden and Iraq.

left: Jews Temporary Shelter moved from Leman Street

to 63 Mansell Street. The building is still there

In 1973 the shelter moved to better and smaller

accommodation in Mapesbury Road in Kilburn, north-west London.

Ironically this move came only shortly before a government

clamp-down on refugees, with the result that a beautifully

refurbished house was under-used and indeed mis-used. The Shelter

had lost its way as a charity.

In the 1990s the trustees re-evaluated the way the

shelter was running. The conclusion had to be that the trustees

had failed to note the low numbers of people requiring help, and the

high cost of staffing a largely empty building. The charity had a

considerable income from its investment and this was now being

wasted.

Eventually a consultant was appointed to recommend a

way forward, which resulted in the shelter’s closure in its present

form. The building in Kilburn is currently leased to Hillel for

student accommodation.

When these changes happened there was a strong

reluctance to lose the physical reassurance of an actual safe house,

a sort of secure house. Slowly trustees accepted that if there were

another crisis forcing Jews to seek refuge in the UK, a single house

in Kilburn with space for a maximum of 25 beds might not be so very

useful and that conserving investments would ultimately offer

greater opportunities for providing emergency assistance. And so

the decision was made.

The investment income of the shelter is now used to

make grants to help Jews with housing-related needs, and emergency

accommodation. Instead of five staff eating and sleeping and

receiving salaries from the shelter we now have an administrator

working 5 hours a week, working rent-free from Hillel’s offices.

My own involvement started in this period of

re-direction and the evaluation process that I have described during

the 1990s, and continues now in the allocation of grants. Every

Sunday morning at 8.45 three of us hold a telephone conference call

and discuss the grant applications from the previous week. Grants

are approved and emailed to the administrator who can therefore

respond to an application in less than one week, making it probably

the fastest functioning charity ever.

But to return to the past, for me the most

spontaneous and moving account of the shelter was written by Stefan

Zweig, mentioned above, a German writer living in London, who wrote

it to accompany a major appeal by the shelter in 1937. His essay

was titled, aptly, House of a Thousand Destinies.